"I have found throwing axes mentioned in a few places. Are those mentioned in England?"

So far, I have not encountered any mention of throwing axes in English sources.

You bring up a good point about translation. In the 14the century London coroners' inquests, those records have been translated and interpreted into modern language. "Daggers" and "knives" were the most common weapons used in those homicides, but without knowing the original words used, it's impossible to know if this is an artificial modern distinction or a historical distinction.

To me, a "knife" is a tool that would be carried for a variety of purposes, most of them utilitarian and benign. While it was often used as a weapon, that was not necessarily what it was designed to be. On the other hand, to me a "dagger" is something that was designed to be a weapon, whether to actually be used as a weapon or more like a piece of costume to represent status or something. But again, that's MY distinction and should not be applied to 700 year old legal documents.

Whether it's the translation or the original document, the London coroners' inquests do give us a little more help. We generally see phrases like "a knife called an Irish knife" or "a knife called a "thwittle" or "called a misericord" and a variety of other terms, where when we see "dagger," then it just says "dagger."

I have no idea what a "thwittle" is, or a "bideu" or a "trenchour" are or most of the other terms that are described as knives. They are knives, of course, but I have no idea what they looked like or what their function was. Were any of them the equivalent of a German messer?

| David Kite wrote: |

| "I have found throwing axes mentioned in a few places. Are those mentioned in England?"

So far, I have not encountered any mention of throwing axes in English sources. You bring up a good point about translation. In the 14the century London coroners' inquests, those records have been translated and interpreted into modern language. "Daggers" and "knives" were the most common weapons used in those homicides, but without knowing the original words used, it's impossible to know if this is an artificial modern distinction or a historical distinction. To me, a "knife" is a tool that would be carried for a variety of purposes, most of them utilitarian and benign. While it was often used as a weapon, that was not necessarily what it was designed to be. On the other hand, to me a "dagger" is something that was designed to be a weapon, whether to actually be used as a weapon or more like a piece of costume to represent status or something. But again, that's MY distinction and should not be applied to 700 year old legal documents. Whether it's the translation or the original document, the London coroners' inquests do give us a little more help. We generally see phrases like "a knife called an Irish knife" or "a knife called a "thwittle" or "called a misericord" and a variety of other terms, where when we see "dagger," then it just says "dagger." I have no idea what a "thwittle" is, or a "bideu" or a "trenchour" are or most of the other terms that are described as knives. They are knives, of course, but I have no idea what they looked like or what their function was. Were any of them the equivalent of a German messer? |

Trenchour means a craving knife, which is similar to the modern German tranchieren for carving meat. Thwittle seems to have been related to the word whittling and meant a small knife. I couldn’t find out what bideu means. Possibly, it is also a type of utility knife.

https://www.anglo-norman.net/entry/trenchourhttps://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/thwittle

| Quote: |

| Trenchour means a craving knife, which is similar to the modern German tranchieren for carving meat. Thwittle seems to have been related to the word whittling and meant a small knife. I couldn’t find out what bideu means. Possibly, it is also a type of utility knife. |

A bideau (or, in English, bidow) is a long fighting knife. It is associated with a type of light infantryman found in 13th and 14th century French and Anglo-Gascon armies, variously Bidet, Bidaut, Bidower. Naming soldiers after their distinctive weapon was pretty common in French and English at the time. IIRC, Froissart also borrows the term to refer to Welsh and Cornish infantry armed with knives.

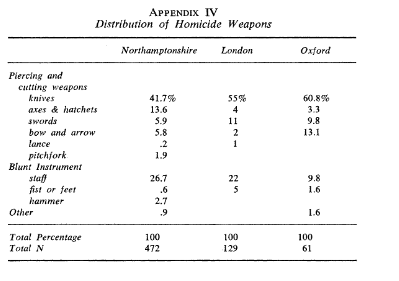

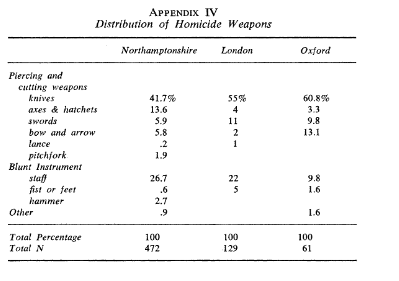

I have chanced upon a comparative murder weapon table for the London and Northamptonshire records, with the added bonus of Oxford thrown in. It is in

Violent Death in Fourteenth- and Early Fifteenth-Century England

Barbara A. Hanawalt

Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Jul., 1976), pp. 297-320 (24 pages)

which is available for free reading on Jstor.

It confirms that knives and staves were pretty common, and the impression that axes were more prevalent outside London. Perhaps wandering around with a pollaxe was more likely to attract unwanted attention in the urban space?

Attachment: 26.2 KB

Attachment: 26.2 KB

Violent Death in Fourteenth- and Early Fifteenth-Century England

Barbara A. Hanawalt

Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Jul., 1976), pp. 297-320 (24 pages)

which is available for free reading on Jstor.

It confirms that knives and staves were pretty common, and the impression that axes were more prevalent outside London. Perhaps wandering around with a pollaxe was more likely to attract unwanted attention in the urban space?

"We also can't take it on faith that just because there were laws that those laws were obeyed, or that they were enforced, or enforced fairly."

This is true. Enforcement could be spotty and it might depend on your status as well. And it might depend on location or the mindset of the local enforcers. I would imagine in larger cities it might be enforced more strictly while in smaller towns or villages it might be sporadic enforcement at best.

Like today you most likely had great variances on enforcement on laws concerning weapons.

And if there was a trial no guarantee you would be found guilty. I remember reading many years ago about how it more common than thought that a person might be found not guilty if it went to trial over an offense.

This is true. Enforcement could be spotty and it might depend on your status as well. And it might depend on location or the mindset of the local enforcers. I would imagine in larger cities it might be enforced more strictly while in smaller towns or villages it might be sporadic enforcement at best.

Like today you most likely had great variances on enforcement on laws concerning weapons.

And if there was a trial no guarantee you would be found guilty. I remember reading many years ago about how it more common than thought that a person might be found not guilty if it went to trial over an offense.

| John Dunn wrote: |

| "We also can't take it on faith that just because there were laws that those laws were obeyed, or that they were enforced, or enforced fairly."

This is true. Enforcement could be spotty and it might depend on your status as well. And it might depend on location or the mindset of the local enforcers. I would imagine in larger cities it might be enforced more strictly while in smaller towns or villages it might be sporadic enforcement at best. Like today you most likely had great variances on enforcement on laws concerning weapons. And if there was a trial no guarantee you would be found guilty. I remember reading many years ago about how it more common than thought that a person might be found not guilty if it went to trial over an offense. |

The biggest question I have about enforcement, is who would enforce it. Knives and dagger were considered a sign of adulthood for non-knightly males. I wonder if it was in the strictest cities, the situation was a little like in Iran, where women don’t always follow the clothing rules, and avoid the police (mostly).

As far as status, I think the list of exceptions written into the law, or the one example of leniency found, shows that high rank or connection certainly played a role.

I am not sure if there would have been much of a trial. I have heard that at a certain time in England, juries wouldn’t convict because the punishment was often death for minor crimes. I am not sure how the German legal system was in Germany in the Middle Ages, but in most cases the punishment for carrying a weapon was a fine, with the possibility of being sent out of the city or imprisoned for a short time. In most cases, the defendant would have been caught in the act with the knife or sword being good evidence against him.

| Quote: |

| I have heard that at a certain time in England, juries wouldn’t convict because the punishment was often death for minor crimes. |

This was later than the Middle Ages. Medieval law enforcement was much more variable, with minor crimes dealt with by fines in many cases. Even killing didn't always lead to the death penalty - a perpetrator could often choose to "abjure the realm" , a formal process of self-exile.

I recently saw this picture on youtube, it is from the Hausbuch Wolfegg. It is a depiction of Mars, but doesn´t depict war, so much as violence. Most of it seems to be feuding, although there is a little bit of murder.

[ Linked Image ]

In the bottom left-handed corner, a pilgrim is being murdered with a dagger. For some reason, an axe lies on the ground. Maybe another typical murder weapon. I think the fact that it is a pilgrim is to emphasize that he is an innocent victim. To the right there seems to be an armed robbery.

In the middle, the various methods of feuding take place. Cattle are being stolen, houses are being set on fire and peasants are being captured. Interestingly, there are weapons present, but are not being used in the feud. The women seem the most aggressive, attacking with pots and sticks. This may be intended for humour, but I think there is another reason. First, it seems that only the male peasants were considered legitimate targets of capture. Second, this form of resistance provides the highest chance of success for the peasants without escalating the violence. In theory, no one was supposed to be killed in a feud (but of course it happened). I believe at this time, feuds were illegal anyway. What the guy with the winged spear is doing, I don’t know. Maybe that he is doing nothing is the point.

[ Linked Image ]

In the bottom left-handed corner, a pilgrim is being murdered with a dagger. For some reason, an axe lies on the ground. Maybe another typical murder weapon. I think the fact that it is a pilgrim is to emphasize that he is an innocent victim. To the right there seems to be an armed robbery.

In the middle, the various methods of feuding take place. Cattle are being stolen, houses are being set on fire and peasants are being captured. Interestingly, there are weapons present, but are not being used in the feud. The women seem the most aggressive, attacking with pots and sticks. This may be intended for humour, but I think there is another reason. First, it seems that only the male peasants were considered legitimate targets of capture. Second, this form of resistance provides the highest chance of success for the peasants without escalating the violence. In theory, no one was supposed to be killed in a feud (but of course it happened). I believe at this time, feuds were illegal anyway. What the guy with the winged spear is doing, I don’t know. Maybe that he is doing nothing is the point.

Page 2 of 2

You cannot post new topics in this forumYou cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

All contents © Copyright 2003-2006 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Full-featured Version of the forum