| Author |

Message |

|

Mark Griffin

Location: The Welsh Marches, in the hills above Newtown, Powys. Joined: 28 Dec 2006

Posts: 802

|

Posted: Tue 14 Apr, 2015 6:55 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 14 Apr, 2015 6:55 am Post subject: |

|

|

Apart from itinerant ditch diggers and what were effectively smallholders i can't think of any medieval trades and crafts that were not governed by a guild system, often down to a very small degree. Now you have equestrian suppliers who cover all the tools, tack and everything else. Then each item had a guild from curry combs to girths to collars to saddlers etc etc and woe betide anyone who pinched work. My favouriteexample is the painter stainers guild who rioted when they found the saddlers painting saddle trees instead of them. 13 deaths in the ensuing street fight as i recall.

As for when the crossbow falls out of favour over here well we of course are mainly longbows and by the 1560's they are really dropping out of service fast. By the time we are helping the Dutch in the Spanish Netherlands they are few and far between.

From 'The Decline of the Longbow' by P Valentine Harris (web article)

| Quote: | It is evident that even good archers wished at least to try the new-fangled weapons, for in 1569 the government forbade trained archers to learn the use of firearms, and in 1577 the Council stated that the neglect of archery was caused by "people imagining it to be of no use for service as they see the caliver so much embraced". The bow in which England had always excelled, was still necessary and again, the Council commanded that illegal pastimes be suppressed. 2

In 1569 bowmen had taken part in the suppression of the northern rebellion and a company of bowmen went with Leicester to the Netherlands in 1585. But in 1589 the Council decided that archers were no longer required in the standard company organization but could be formed into their own companies. In 1595 the commissioners of musters in Buckinghamshire reported that they had begun to convert some of their archers into calivermen and musketeers. The Council instructed them to have all known bowmen so converted3 One can imagine some good archers grousing, but most of them would be willing to try their hand: the desire to be in the fashion, to go with the crowd, is part of human nature.

Herefordshire required only archers "suche as are both Lustye in body, and able to abyde the wether & can Shoote a good Stronge Shoot for heretofore we have alowed manye Simple [frail, delicate] and weake." Huntingdon pleaded for a smaller quota of archers as of many who attended the butts as required by law not more than 100 were competent.4 Reluctant soldiers could affect inability to draw a bow when the commissioners were around. |

of course that doesn't mean to say the gunners were of any use...

| Quote: | | But it was not only archers who were found to be inefficient. In 1569 Lord Clinton, marching north, complained that his harque- busiers ought to stay in Newark as they were not trained, and two years later Sir Henry Redecliff found the 100-strong Portsmouth garrison the worst he had seen. "Amonghtes three and twenty which were alowed to be serviceable, not fyve of them shott withing fyve foote of a marke being sett within foure score yardes."5 |

Currently working on projects ranging from Elizabethan pageants to a WW1 Tank, Victorian fairgrounds 1066 events and more. Oh and we joust loads!.. We run over 250 events for English Heritage each year plus many others for Historic Royal Palaces, Historic Scotland, the National Trust and more. If you live in the UK and are interested in working for us just drop us a line with a cv.

|

|

|

|

Jean Henri Chandler

|

Posted: Tue 14 Apr, 2015 8:14 am Post subject: Posted: Tue 14 Apr, 2015 8:14 am Post subject: |

|

|

William, please forgive me if I answer in a somewhat roundabout way.

As Mark pointed out, craft guilds regulated most though not all forms of production in the medieval world, at least to some extent. More specifically, and more relevant to the topic at hand, almost all the higher end export products were controlled by guilds. Nobles and Church entities also organized unskilled manufacturing in was was called the 'putting-out' system but that was usually for more low-end goods, the Wal-mart of the day.

I don't know the exact process for crossbowmakers or gunsmiths but I know how it worked for sword makers, and maybe this would serve as an analogy. The main craftsman would be the cutler, messerschmeid in German-speaking areas. He would typically get an order either through the guild or from a merchant (or from a merchant guild) or sometimes directly from a prince or the town government or some other entity. Say for 100 swords. The cutler would first make a design for the sword, if we agree with Peter Johsnnson we would say based on the geometry of Euclid and Vitruvius. The cutler would then subcontract his design out to other cutlers, sufficient to handle the business in time for the deadline.

Guild rules typically limited the size of each workshop to one master and his wife and kids, plus a handful of apprentices and journeymen so this was necessary for big jobs (in fact it was routine). So he would buy 100 sword blanks from a foundry (usually mass produced in a bloomery forge). He would distribute these to the other cutlers. Each cutler would in turn send these to a blade maker in batches of 10 or 20. The blade makers make use of guild workshops with water-powered triphammers and so on. The cutler would meanwhile choose wood to make hilt components and scabbards and so on. As the blades came back from the blade makers they would be sent to sword sharpeners (who would use sharpening wheels), and as they come back from the sharpeners , they would be assembled, cross and hilt put into place, pommel peened on and so on. Scabbard makers would be hired to make the scabbards. Finally they would send the completed swords to sword polishers in batches of 10 or 20.

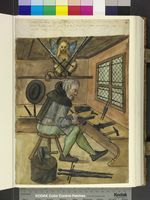

Usually when you see period images of cutlers they are assembling finished swords and daggers in this way. For example this guy with the Lion of St. Mark in the background. The guild and town governments were very concerned with quality control so as to maintain the reputation of their valuable export industries so they would conduct regular inspections of workshops and had standards for the materials (metalurgy) and processes so on. With the guild system shortcuts were prohibited.

But craft-guild systems varied a lot depending on the dominant industry in the town, and if the town itself was an export oriented manufacturing town or not. Some industries like textile weaving (Ghent, Cologne, Florence) and armor production (Milan, Brescia, Augsburg) got so sophisticated and specialized that their production for export was dominated by a few towns. Others like beer brewing and sword making were done in many places or in whole regions.

Towns without strong export / manufacturing industries often had weaker guilds and less specialized production networks. And only some areas had a lot of export industries in their towns. England for example didn't do a lot of exporting of sophisticated finished products; it was mainly a major exporter of raw wool, which was processed by the textile industries of Flanders and Lombardy, something England hotly resented and tried to address, but didn't really succeed at until the end of the medieval period.

I'm not sure if gun or crossbow making was something which was so specialized that it was dominated by (if not unique to) certain towns or regions, but there are some hints that it was. I know that Venice had sophisticated and well regulated crossbowmaking industry, and later on the Venetian arsenal contracted out to make guns. Nuremberg also seems to have been a center for firearms manufacture, and they were also made in some numbers in Prague, Ghent, Bruges, Cologne, Krakow, Gdansk, Wroclaw, Bologna, Milan and Florence, among other towns.

Guns seem to have remained fairly expensive through the medieval period, and until the advent of corned powder in the early 15th Century, (and the gradual dissemination of the technique through the 15th) it took someone highly specialized experts to even effectively use guns. Mercenaries who knew how to shoot were paid a lot and were in high demand, the gunners in the Hungarian Black Army for example were paid almost as much as lancers. Most late medieval armies in central Europe had a specialist expert called a 'cannon master' who was in charge of the powder and the cannons, and usually also inspected the handguns. Also highly paid.

This is a crossbomakers workshop from the Balthasar Behem Codex, Krakow 1505

I know that in Central Europe in the mid 15th Century a crossbow cost about double what a sword cost, roughly 1 mark vs. 1/2 mark. I believe a firearm was roughly comparable to that in price, widely depending on the type and any extra features like special locks. But industry at this time could be focused three ways, luxury goods, higher end goods for the wealthier markets (most typical for export), and mass goods for the broad market. Guilds often reorganized themselves to deal with changing economic conditions along these lines, depending on the market conditions. For example the Venetian glassmaking industry shifted from making drinking vessels, mirrors and eyeglasses for urban consumption in the 15th Century to making glass beads and trinkets for trade with Natives in the New World in the 16th. I think firearms production shifted toward the latter (low-end) in the 16th Century (though there remained a smaller high-end 'luxury' gun market as well).

By the mid 16th Century, really starting after 1520, a combination of factors had changed the picture.

1) Crossbows had reached the design limits of their power.

2) Crossbows were hard to make cheaper (they were close to the efficiency limits of their manufacturing processes)

3) Gun production had become standardized to some extent and guns were still getting more powerful and efficient. Using less specialized components than crossbows, they could be scaled up faster.

4) Gunpowder production had been made vastly more efficient and standardized

5) Guns had gotten much easier to use with the matchlock and corned powder

6) Methods for drilling ordinary people to use guns with reasonable efficiency (something which was not as easy for military grade crossbows as they claim on the History Channel or the BBC) had been developed.

7) The Atlantic-facing kingdoms got an almost unlimited flood of wealth from the New World and the opening of the Pacific, chattel slavery and the rest, shifting the balance of power westward.

8) These were used to set up mass production 'putting-out' systems of mediocre but serviceable firearms.

9) Using the new drilling techniques and utilizing one of the simpler gun designs of the time as the baseline (the simple matchlock) these Atlantic kingdoms could produce large armies of low-paid pikeman, handgunner and cannon which could defeat smaller, much more expensive specialist type armies of the earlier eras.

10) This meant the replacement of not only crossbowmen, but also armored knights, and many other types of specialists.

However archers still had a niche on ships apparently for a while. Some historians date the decline of the naval power of the Ottoman Empire from the massive loss of skilled archers at Lepanto. The presence of so many powerful longbows on the Mary Rose also suggests that the longbow still had a role in naval war even that late in the game. And similarly heavy cavalry took a while to phase out (arguably the Polish defeat of the Turks in the 17th Century was probably the last major use of it). Adoption of pistols as well as or as a replacement for lances helped continue the role, though the rapid decline of the armor-making industry after 1550 meant that body armor had quickly become much less efficient and heavier.

Firearms technology reached an early peak around the late 15th / early 16th Century, with rifling, breech-loading, and the wheel-lock and so on coming online, but the much simpler (and often though not necessarily always cruder) matchlock firearms came to dominate the battlefield for the next several centuries. This was the 'sweet spot' for the new breed of autocratic Western Kings. Armies became about a kind of economy of scale and unskilled labor more than small forces based on specialized skilled-labor. In terms of production, from 1520-1780 the 'putting-out' system very gradually replaced the craft guilds, especially in the colonies, and in the colonies in fact many things were being made with slave labor by the 17th Century, including probably firearms.

In other words, I think the shift was at least partly a socio-economic one rather than purely technological.

Jean

Books and games on Medieval Europe Codex Integrum

Codex Guide to the Medieval Baltic Now available in print

|

|

|

|

|

|

You cannot post new topics in this forum

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

You cannot edit your posts in this forum

You cannot delete your posts in this forum

You cannot vote in polls in this forum

You cannot attach files in this forum

You can download files in this forum

|

All contents © Copyright 2003-2024 myArmoury.com — All rights reserved

Discussion forums powered by phpBB © The phpBB Group

Switch to the Basic Low-bandwidth Version of the forum

|